Medium

Identificação

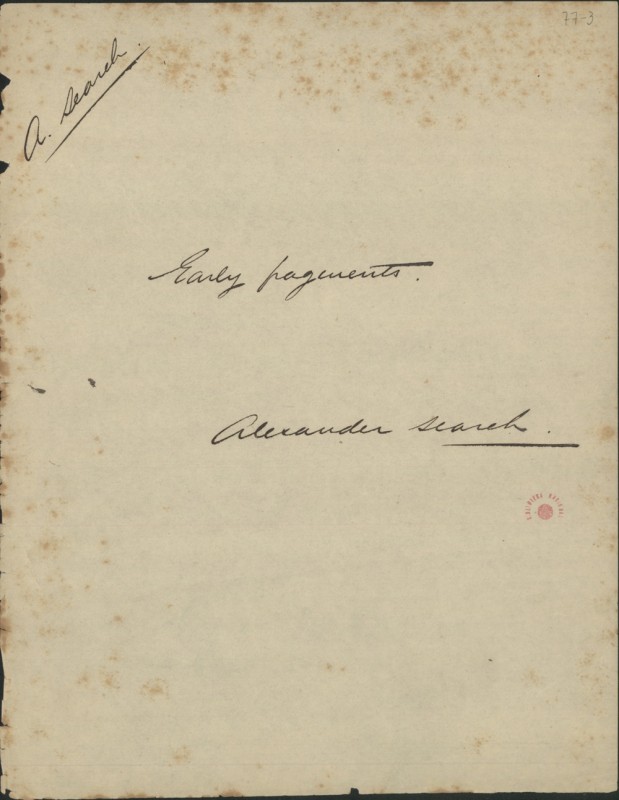

[BNP/E3, 77 – 3-46]

A. Search.

Early fragments.

Alexander Search.

[4r]

Early Fragments.

I.

– “What is fame after death?

A life that’s not a life, my dearest boy,

A life we live and yet cannot enjoy,

A name writ at the corner of a street,

A bust that we can crush beneath our feet,

A light wind that a tempest makes forget:

That is fame after death. Cursed they who fret

But to attain it; and they who die for it

Kill themselves twice, Marino. Therefore, hear,…

1903.

___

II.

‘Tis pleasant to be loved by all,

‘Tis sweetest to be loved by one,

But there’s in life no greater gall

Than to be loved by none.

1903.

- III -

The blackest clouds are never packed so tight

That we see not some blue,

The sky is ne’er so dark some ray of light

May not break trough.

1903.

[5r]

Early Fragments. 2.

- IV. -

Nought is more cold than ashes are,

Yet there a fire hath star

The night around a lonely star

More dark than all is seen.

– V –

Song of the Obscure.

What care I for the fame of the glorious and great?

What care I for the stars that on other worlds glow?

Though I’m poor, and unknown, and is humble my state.

If I have but few friends, yet I have not a foe.

–1903–

– VI –

“Say thou not so.

The meanest wretch is human and can feel

E’en as thou canst; has heart and head like thine;

Can calculate, can suffer, laugh or weep;

And thou he loves and hates, and is as thou

Strong in his virtues and in his faults weak.

And nothing can distinguish high or low

But birth, a matter of a wav’ring chance;

But as for heart, Marino, ‘twold be well

If all our nobles and plebeian hearts.

[6r]

Early Fragments 3.

Mar. Too true thou speakest, and I see I err;

If all our mighty men had nearer hearts

Would Satan have a nearer following.

1903.

– VII –

- Who art thou? I pray thee and stand not there

As if hadst thy mind to go no farther.

Mar. Who am I?

Thou askest well indeed, since I know not.

A month – a week ago I could have said

With ready mind and joyous – “I’m Marino”…

But now I cannot speak;

My mind is so much stronger than my tongue,

That wags is not, but rather holds it back.

Who am I?

Indeed thou askest well. Full many a time

I asked myself that question, and no answer

Could my mind give to what my tongue did speak.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

My mind’s so whriklèd, dashed and spun around,

That what it knows it cannot state aright,

And what it states aright it does not know.

Ah! Foolish me who thought

That logic could have soothed my sad heart

And I could less my sufferings by reason;

[7r]

Early Fragments 4.

That gayest mirth could choke and make forget

The deepest agonies of saddest heart;

That wine and sleep could dull.

What themselves keep not off.

How can I reason when no reason’s left?

How can I think when more I bend my mind

Towards one object it doth show another?

When mem’ry fiendish grows and doth neglect

To give the secrets that it treasured up.

Thou sayest I’m Marino… Art thou right?

Resolve me then, since I cannot resolve

The simplest problems of a querying mind.

To-day a friend did pass and called to me,

Saying “Marino, thou art changed indeed”;

I looked full well at him and saw him not,

But saw a black and yawning awful chasm

And knew that I was looking in my brain.

1903.

– VIII –

Ye spirits of the horrid night,

Ye phantoms of eternal space,

Spectres of time, that hold your place

Beyond the scope of human light!

Listen unto this song of woe.

1904.

[8r]

Early Fragments – 5.

IX.

His powers were great but faulty, for in fact

Though he had feeling yet he wanted tact;

Clever he was, but spent his easy rhymes

In being the scandal-monger of his times;

None was so safe his tooth might not indent;

Slander he used so well that, by indent,

Became mere slander in a few small hours.

Who would deny therefore his useful powers?

1904.

X.

Here lies old Jones, now gone to endless light;

All day he idled and he slept all night,

But of his time the rest he spent aright.

1904.

XI.

Marino: The mystery of all – it lies around,

It lies beneath, above, in all the earth,

In all the sky and more – why, dear Vincenzo,

Lies it not here within – in our own heart?

Its answer too is written on all earth,

On all the sky and more, but we do lack

To know the language wherein it is written.

That we shall never know.

[9r]

Early Fragments –. 6

Vin: A giant cypher

Whereby the key is death.

1904.

XII.

Vincenzo: Verily there is not

A thing more greater than the mind of man:

All worlds that are it hath long visitèd,

All worlds are not it hath long visitèd,

All worlds would be it hath long visitèd.

Marino: Yet how much lacks it and what imperfection

At every thought appear! Why then my friend,

If that thy mind hath space then let it grasp

Duly the greatness of this ambient space

In which that clouds are but as grains of dust,

The sun a candle and the moon a match

If that they mind hath bound let it confine

All this and state where space doth have its bourne.

Let is find limits to the reign of night, and end

To that of day. Let it but think, weak particle,

And feel the unbounded greatness of the around,

Symbolic of its God and unaccountable,

Beyond the understanding; sight, imagination

Beyond all man.

If that thy mind hath number, let it count

The unnumbered worlds that gem the silent air,

[10r]

Early Fragments – 7.

And the untold stars, in cohorts bright and long,

That blink at night, as if in sleepy joy.

If that thy mind hath depth, then let it pierce

This earth of matter and distinguish what then

Doth lie within its core. Of thy mind hath thought,

Then let it pounder on its own existence

And lay thy hand upon thy head and say

“Here is a head”, upon thy heart and think

“Here is a heart”, and glance upon thy limbs,

And know what all that means. For thou wilt find

That man so droll is in his strange existence,

So strange his fate, so obscure his procedence,

That with so simple problem we are dumb.

So laughable, so quaint, so real, unreal

And yet so sad! How to express it all?

Had I a thousand tongues, a thousand ways

To say my thought, and but a thought to say,

Yet should my mind oppress me with a thought

That curses language.

Ay, sometimes I think

I am upon the answer of it all; yet then

There doth appear something too horrid in’t

A widening madness, a sickness of light,

And I am dumb.

When I do ponder on

This great, this silent, this unending space,

[11r]

Early Fragments – 8.

I feel as feels the traveller in dizziness

Who looks upon some pit of bottom reft,

In darkness clad, from which sounds horrid clang –

So clangs upon my mind the solemn sound

Of weighted thought.

I’ll give thee aught to think, take but one word

A small word, friend; take thou the word “God”

And tell me all that’s in it. Nay do not tell

But think alone.

1904.

XIII.

Minstrel: I know thee so well, Giles Attom, that thou

Know’st not thyself as well as I know thee;

Thy childhood and thy youth, thy manliness,

Are all to me cognite; thy fathers too

Were both well-known to me; e’en of thy life

I know the secrets all – thy passions, cares,

Thy loves and woes, thy rages and thy calms,

Thy flames and colds, thy present life I know,

And likewise is thy future known to me.

Giles: How? Who and what are thou that canst thus speak?

And claimst knowledge of all?

Min: It matters not

Who and what I am. ‘Tis enough to tell thee…

1903.

[12r]

Early Fragments – 9.

Marino: Back, back, back, back! Thou treacherous sea, move back!

Dost thou not see Marino? Move thou back!

How canst thou be so silent when thou cam’st

To mine own death? Yet now see, Master, see

There is a way down there – dost thou not see

Down there, down there; see how the water shirks it!

Alas, it is a rock! Ah, let me climb

Up this steep cliff; ah, surely I can hold…

Alas I – creep back – rush back, thou awful sea!

Seest thou not I am here – I Marino –

I am not going to die – move back, move back!

(Curses everything. Sees demons and faces. Strives to climb the vertical cliff).....

‘Tis but the last hope of extreme despair!

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Their arms are gripping me and I move back!

Master, thy help! Accurst be thou! Thy help!

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I die, I die! Curst be thou, Master.

Cursèd be Hell, cursed be Heaven, twice curst be God!

1904.

XV.

Happy so soon to die! Thou canst not know

Base human cares and woes and lusts and fears,

[13r]

Early Fragments – 10

And all that hate and love make here below

Of horrors, pains and soul-exhaling sighs

And unavailing cares and useless tears.

Never shall human woes offend thine eyes,

Nor horrid doubtings of another world.

Nor ever shalt thou mourn a careless youth,

Nor shall thy soul be torn, thy thoughts be hurled

Beyond the mazes of a confused truth,

Nor shall thy soul at last in vain seek pity and ruth.

Ah, never shalt thou known what ‘tis to strain

A mind to language and to speak a soul,

When every newer feeling brings a pain

And every thought yields not its glowing whole

But breaks the lands of self and runs from thy control.

Nor ever canst thou thirst for aught above

Things of this earth, fair to thee while didst live;

Thou never shalt require a heavenly love

Nor ask from earth what earth can never give.

1904.

XVI.

Small is the grief can find its vent in tears;

When thou canst weep is marked thy sorrow’s fate:

Mark how the rolling thunder doth abate

[14r]

Early Fragments – 11.

When fresh’ning rain the sultry weather clears.

Tears are the taxes paid on joys bygone

And joys to come (if joys do e’er return);

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1903.

XVII.

One hopeless love another love can smother,

Lost love another love can make forget,

And e’en although thy grief seem endless, yet

Thou’lt cease to weep one day, unhappy mother!

Time heals all woes, and thou wilt find it so

When years have past, in hours of happiness,

Thou wilt forget, nor wilt thou laugh the less,

Thou wilt forget, as if thou hadst no woe.

When raven night brings down her thoughtful

Upon her wing, ‘tis then the time to weep.

Thou’lt wonder how thou e’er couldst laugh and keep

Attentive ear to mirthful joke and song.

And yet ‘tis thus and well: the human mind

Dwells not for e’er upon one thing alone;

Nightly resolve and midnight tear and moan

[15r]

Early Fragments – 12.

Fly with the shadows as a straw in wind.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

And yet ‘tis better thus, to leave the world

And not have known how sweet is life to man,

Not to have known its brief, unequal span

Not to have seen those golden dreams unfurled.

Death, ah! the very word is lek a moan

In ghostly darkness, when all men are still.

All that it means, or may, is ‘nough to chill

My very mind and choke my rising tone.

1903.

XVIII.

Death came and took him who lived by my side.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Methinks (so near and known he was to me)

In this so near appearance of cold death,

I felt upon my cheeks the sultry heath

Of the great vortex of eternity.

So near to me, Death’s hand seemed e’en to touch

My starting frame; it seems to me in pain

That Death near to me will not come again

Unless ‘tis for myself....

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

[16r]

Early Fragments – 13.

Some die upon the bloody battlefield,

Some doth the scaffold take, and some the knife,

Others resign their being without strife;

Martyrs yet others do their being yield.

Some on a couch of pain resign their breath,

Others by deepest grief are torn away,

Some go e’er they have known the lovely day,

Some die too late. But death is always death.

October, 1904.

XIX.

To-morrow shall become to-day,

To-day for e’er shall go;

The passèd sun of yesterday

Was far a year ago.

And yesterday was once to-morrow;

Those days of joy or days of sorrow

That hundred years or so

And distant yet from us, shall come

And pass for ever to their tomb.

The modern times of no romance

More modern times shall follow…

Frail things of earth, so strange and sad,

[17r]

Early Fragments – 14.

Shall ye all pass away?

Must all these things of love and glad....

1904.

XX.

Do thou amid the laugh and song

In stately halls and fair

Remember that despisèd throng

That lingers in despair.

Amid the dance, when tuneful sound

Doth sway the pleasèd mind,

Mind thee how many lie around

To pain and grief confined.

Last virtue of a wicked man

Is pity: have it thou!...

1904.

XXI.

On those hill-tops sombre foliage crowned

There rules the beauty of a castle old

Whose towers torn still sway the heated air,

Whose walls in ruin bare

Grin at the beauty of the world around

And ‘neath the sun itself are turned cold;

[18r]

Early Fragments – 15.

For what avails it if the sun’s live gold

Can stain the blackness of the dungeon’s night?

It makes it but less bright…

1904.

Woman (to Marino):

Some men have darkness in their countenance,

Their eyes respond not to the glancing light

But are in shadows bathed. But thine seems

The sultry darkness of the tropic night

Where lightning is to be…

1904.

XXIII

Thus when I rove along the fragrant field

Everything to me such pleasure yields.

The blades of grass, in graceful curve aslant,

Have their sweet, springful and melodious chant.

Nothing is dumb: with furious voice enorm

Its rude advice doth give the staggering storm;

The trees, whose rustling ceaseless to the breeze

Seems as the hissing of the summer seas,

Tell wonderous tales of easy, pleasant bowers,

Which also tell the bright and early flowers.

These pleasures do thou but allow thy mind

[19r]

Early Fragments – 16.

And when thou readest thou wilt surely find

Books are but Nature’s thoughts in dress diverse,

Though never better, yet too often worse.

1904.

XXIV

Nothing is dumb; the smallest thing can speak

In varied tones, in accent strong or weak;

Learn then to hear and then shalt thou rejoice

To find in ev’ry thing a pleasing voice;

The storm to thee will speak, the changeful wind

Shall tell thee secretes running unconfined;

The book shall babble many a joyous tale,

The trees shall whisper and the sea shall wail,

Every field and plain in every land

Shall tell its tale – if thou but understand.

And silence too can speak and, if thou hear,

When night falls slowly on the landscape drear,

Voices unheard shall wonderous secrets tell

And dead men jabber in a curious spell.

Commune with Nature; let thy thought be one

With Nature’s voice…

Wonder not then that I love solitude:

Men’s voices are insipid and are rude,

Most to me, on whose grave this should be seen

Thought was his curse, expression was his bane.

[20r]

Early Fragments – 17.

XXV.

The Atheist – I.

Slow rises in the East the glorious golden orb

And the whole earth and sky he seems now to absorb

In his fertile embrace; he rests on field and town

Wreathing them in his glee with a flammif’rous crown.

How gleams the sea beneath his fiery, joyful light!

How both mountain and vale seem so superbly bright!

With what joy too the peasant greets the merry sun,

For comrades old they are: their morn’s always begun

At the same hour, and, when Apollo sinks to rest

With all his galas in the far and ruddy west,

He too his fireside seeks, his happy rustic home,

Where nought may be but bliss, where but the pure may roam;

More than an epopee is worth their simple story.

How like the dreams of youth is the sun in its glory!

In grandiose pump he sails the azure firmament,

Like an angel of light, by God’s command us sent;

But slow – more slow – he sinks: no vestige of his light

Is seen and earth fall the awing shades of night.[1]

So in our soul it is: our youthful dreams pass by,

Raising our hopes to heav’n, our expectations high;

But soon they disappear – not even their pale ghost

Can we see, for they are in utter darkness lost.

But in common one thing with the red sun they lack:

[21r]

Early Fragments – 18.

After the cold, dark night the shining orb comes back,

But they return no more.

Enough! The sun’s bright beams

That shine on the gay world, on rivers and on streams,

Alike in the poor’s roof as on the palace dome,

Rest beautiful and clear on the city of Rome, -

Call’d city of the Lord, but ownèd by the devil,

Termed city of the good, but the den of the evil –,

And its solacing light to cottage and to hall

Makes stand out bold and grand that wonderous cathedral…

1903.

XXVI.

Coul I, oh orb of deathless light, be constant as thou art,

And joy and kindliness could I to every home impart,

Coul I be bright and bring always a blessing to each man,

I might not weep, with vain despair, my life’s too shortened span;

But I am not, as thou art, gay, nor constant as thou art,

To do good I’ve no power, oh sun, but have a kindly heart;

I waste in tears from man the power that I have to do good…

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Oh, glorious orb that fillst the sky in spring when man is gay,

Who most remembered art by us, when thou art gone away;

How do I yearn for thee to-day; in winter’s cheerless sky

I find a something like myself…

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

[22r]

Early Fragments – 19.

Immortal orb, oh thou hast too, full many a year ago,

What sights hast seen, what horrors seen, along the times’ cold flow?

Thou show’st perhaps one day upon the bloody Grecian green,

Thy orb when Troy’s old fleet was broke along the sky was seen;

Thou’st seen the rise of powers immense and shone upon their fall;

Thou’st marked the birth of emperors and smiled upon their fall.

Thy blazing car maintained its speed when man in tears was found.

Tell me the tales, oh sun, thou’st learnt in earth’s far distant round.

1904 (October).

XXVII

… The doctrines too of

Pythagoras, of holy Socrates,

Of spokesman Plato, shallow Cicero

And many more. Have I not pored in vain

On antique texts of dark and woeful lore. Have not sages

Spoken to me from woe-wrought solemn pages?

And yet I nothing know; the more I read

The more I am confused and bewildered…

-1904-

XXVIII.

– Old James is dead, who did his work full well;

Ought he to go to heaven or to hell?

- James was a thief; his work was done too well;

So, unless into heav’n he stole, to hell.

– 1904 –

[23r]

Early Fragments – 20.

XXIX.

Translation from Catullus (70).

My sweet swears to love none but me,

That Jove would beg her grace in vain;

But what a woman tells her hungering swain –

Oh, write it on the winds that flee

And on the swift waves of the sea.

January 1905.

XXX.

There was a time when sacred things

Existed, but modernizings

Have made them all go wrong and hookèd,

Twisted, doubled-up and crooked.

Before, divine things were not made

The articles of scribbling trade;

Now, for the good of halls and hovels,

They put the Passion into novels.

- 1904. –

XXXI.

With gesture slow and deathsome eyes she came

As with some sultriness and languid limbs,

Her from half-nude, her half-dishevelled hair

Beauteous in its disorder, and her face

Half-calm, half-flushed, as from an amorous couch.

– 1904 –

[24r]

Early Fragments – 21.

XXXII.

Translation of Fourth Georgic, lines 116 et seq.

Myself, so near my labour’s end were I not even now,

Furling my sails, and eager too to turn to land my prow,

Perchance those fertile gardens fair which the careful tendings clear

Would sing, and Paestum’s rosetrees too, which blossom twice a year;

And in what way the endives joy to drink the rills that pass,

And green banks in their parsley, and how, trailing through the grass,

The gourd doth round him to a paunch; nor had I held my tongue

Of blooming-late narcissus, or acanthus supply-swung,

And white-streaked ivy, and myrtles too, their lovèd banks among.

- 1904 –.

XXXIII.

Many and great the things that men have said

But those are greater that remain unspoken –

The night holds more than noisy day of dread

And loves and woes and torments sweet or dire,

Of passions hushed in climax, and of broken

Hearts in the breaking silence…

– 1904 –

XXXIV.

Translation of the Fourth Georgic, lines 149-152.

Come now, th’instincts which Jove himself gave bees I will explain

At once, as reward for that they, following in the train

Of the Curetes’ tuneful sounds and clanging cymbals, gave

The food they brought to Heaven’s King in the Dictaean cave.

- 1904 –

[25r]

Early Fragments – 22.

XXXV.

Nothing is mute; all nature speaks to me,

The crashing waters and the silent tree,

The sea, the birds, the dumb and curious flowers

And little insects whose life is but hours.

To me they speak, they sing, their voices rise

To me in varied accents doubly wise;

With many a worthy thought and precept gay

To me their voices rise in glad array.

1904.

XXXVI.

But with no settled thought on Nature look

Else ‘t will but echo what thou think’st…

And some sweet rose in fragrance plenteous spread

Will tell thy mind some tale of sorrow dread;

Approach this altar with a vacant mind

And yet prepared; too soon then shalt thou find

How ev’ry thing can speak in its true voice…

But Nature though it speak thus, thus always,

Yet but one thing in many ways doth say.

1904.

XXXVII.

(translated very freely)

Doctor Jack Augustus Carr,

[26r]

Early Fragments – 23

A lawyer in phases deft,

Defends prisoner at the bar

Who is accusèd of theft.

The latter, whose name is Black,

A gent of suspicious fame,

In the lands of Doctor Jack

Had placed his case and good name.

Doctor Jack, a clever man,

When it was his turn to speak,

In his usual way began

Calmly addressing the beak.

“My client, your worship, is

A good man. A soul as true

You will never find as his

If you travel till Peru.”

With a happy gesture slack

Gracing this discourse most able,

He gives the inkstand a thwack

And spills the ink on the table.

Then, with a finger all dark,

While making a motion sleek,

[27r]

Early Fragments – 24.

He leaves an inky black mark

Branded plain on his left cheek.

Then on the ink he had spilt

He places his hand in full,

Leaning forward and the guilt

Of his client thus makes null:

“The prisoner who here, I ween,

Through spiteful enemies stands,

Shows a past life just as clean

As are at present my hands.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1903.

XXXVIII.

So great his will he nothing left undone

Unless it were that which he ne’er begun;

So great his powers he everything embraced

From an intention to a woman’s waist;

To everything he got he ever clung,

So may the halter to his neck when hung.

1904/1

XXXIX.

Laid under leafy canopy at noon

[28r]

Early Fragments – 25.

The lonely poet, in half-waking dreams,

Mayhap in sloth shall hear

Sounds such as night doth offer to the moon

And childly songs of morn,

Sounds not of earth and many a heart-heard moan

And music such as draws the sudden tear,

Receding foam from shadowy rocks lovelorn

On murmurous seas by gleamless shores unknown.

1904/2.

XL.

The day is bright, the skies in glory smile,

In verdant dress the cheerful woods beguile;

The bees at work expect no early showers

But reap their harvest from the purple flowers,

The many birds in graceful discord join

And all their joys in varying song define;

In whispering joy the zephirs’ breath inspires

The youthful lovers into laughing quires.

1904/IV.

XLI.

{…}

[29r]

Old Castle – 1.

Fragments of a poem called

The Old Castle.

I.

Man, strange embodiment of Nature, proud,

Ephemeral creation, can I look

Untouched upon thee, can I calm survey

Thy joys and pains, thy struggle through this world

And last long closing of thine eyes in death?

I love to contemplate thy ways, to gaze

Upon thy haunts, to search thy home, to find

In all thy little actions aught of great.

For I can feel in me a sense sublime

That I was born to think, was born to feel

And not to look in vain at all that is;

In hours of rest and coolness I have felt

A noble exaltation, in my heart

A joy unknown arose, and thankfulness,

And in my eyes the sudden tears’ surprise;

Wherefore I do not know, but when I gaze

Upon this compact and emmoving all

I see behind some force of power enorm

Whose face is as a music strange and full

That lifts my heart above, and moves me past

The bounds of human reason; ‘tis a music

[30r]

Old Castle – 2.

That wraps me round with a forgetfulness

Of common things and thoughts common as they.

(1904).

II.

…oh, man…

Thou wast not made for pain, unthinking fool,

In thy true state, thy mind not made to attempt

To grasp the limits of mending space;

Wherefore shouldst thou, that dost not know thyself

Nor know thine earth, survey the upper air,

The varied changes, life and death and all

In curious query? Oh thou wast not made

For useless thought; thy fame is not attuned

To hold the ravage of all thought, or sway

Creation; yet thou art so very great!

Has not thy mind enslaved all earth again?

Rulest thou not all beasts, thyself a beast?

Oh, thou art strange indeed! Could I explain

Thy meanest action, could I mete thy thought

Or claim thy heart I’d hold myself too great!

Had I an epic’s force, inspirèd might,

I’d sing of thee, but the sublime fits not

A modern soul. Yet I have loved to think.

III.

On that fair land

[31r]

Old Castle – 3.

That flanks the blue Tyrrhenean, or the shores

Of dark Arabia, or fair Illyrian land,

Or where the warlike hosts that met at Ilium

Were born; or where mayhap the brutish Goth

Or brutal Avar, or the fiendish Frank

Had risen, or whence arose the race enorm

Of Boadicea? Themes too strong for me.

No, I shall sing of one long-shattered castle

I once beheld in beauteous Spanish land;

A castle old it was, in times of old

This was no broken race, the strong Iberian

Lay not beneath the yoke of years. Now age

Has broken all his might. Yet let me tell

Thy worthless tale in worthless numbers, I

May thus at length unburden my sad soul.

(1904)

(1904)

IV.

A meanly strain

Fits best a little mind; I shall not wish

To grasp great things; I shall not tell of souls

Or wars and jars and horrid faction rent

In myriad atoms! I can better sing

Of some small matter, of an ancient castle

I once beheld in pleasant Spain, which crowned

A steep, long will, amid the foliage thick

Adorning, lording the subjected vale.

[32r]

Old Castle – 4.

V.

One summer’s day when scalding noon had rung

Across the fields, when lovely cottages

Grew whiter in his gleams, when songs of birds

Broke through the natural stillness, I betook

Myself to a valley, in the Spanish land.

It was a lovely scene, the grass beneath

Of violent greenness fertile, ornamented

With flowers, the bills that girdled all the plain

Seemed as the tiers of seats that piled rose

Within a Roman circus. Near to me

Thickwooded stood a hill, on whose high top

A miserable vestige of ruin

Could scarce be seen, seemed a passage cut

Through all the foliage, yet I thought my steps

Might tread with profit that untrodden ground.

(1904)

VI.

I mind me now

To have heard a tale they know throughout the land.

An old man told it me, I well remember,

An old man, to the village he belonged

That whitens yonder hill-side, and he said

His fathers knew the rustic, simple tale.

The old man it me, and, while he spoke,

He wept I wept to hear him too. He said

[33r]

Old Castle – 5.

That when these castle walls, which I now see,

Were but half-ruined, here lived a gentle maid.

She was the last of that long line, the proud

Line of the Spanish knights, and here she lived

Alone, her father in the boiling sea

Sought for his fame and died – the strong indeed

Sinks to the stronger – and her mother too

Long years of toil had torn from lovely earth.

This maid was named Dolores – ah, that name,

That sad, strange name Dolores! Ah, that name!

There lived here too a cousin; he was one

Of a collateral branch, and he was too

Eager for fame, for love, unfearing death.

She loved him and he loved her; they alone

Remained on earth to each other, and the sky

Might from a smile, and Fortune be adverse –

But what was that to them? At morn they walked

Along the flowery dales and rivers’ banks

Speaking their dreams, he tall and proud of mien,

She tender leaning on his shoulders’ breadth.

And so their morn was past, and when the sun

Stood high in heaven and made the trees more green,

Some bower awaited, and they there would rest

And talk of trifles and of war and lore.

When evening came then they went forth and roamed

Again upon the fields, while coolly came

[34r]

Old Castle – 6

The night’s slow mantle o’er the earth, and then

Hatless they trod the dales again for home.

But ah! What time it was when night did come;

Then by the moonlight, softly pausing lightly

Over the adjoining ruins, they there walked

And dreamed again. These shattered stones recalled

To his mind the deeds the men whose castle this

Had been had wrought, and in his mind his land

Against the invading Moor did bear a lance;

Or now his eyes perceived in dream the boil

Of battle and he walked with joyous strides

The crumbling earth, while she sat near adoring,

Admired his aminated gait; she too

Dreamed oft of her fair cavaliero’s fame

Which, borne upon the wings of language, reached

The distant shores of Albion. Thus they passed

The days and nights their lovèd ruins among;

And yet to him it seemed that fame had called

Him to the fight, and on a summer’s day

He said farewell to her, for he had heard

The neighbouring Lusian on the hated Moor

Was to advance. He kissed her by a stile

Yet not a stile, but something like a stile

That bordered on the long-drawn road, where they

Were wont to sit before, and then he went,

Turning at every step, and waving back

[35r]

Old Castle – 7.

To her whose mind was filled with joy and woe.

He joined the Lusian host, that Lusian host

Which young Sebastian led in joy, which soon

Came to the land it sought, and ere the night

Lay torn and scattered in the Arabian plain.

She heard and wept not, for his beaten corse

They did not find, nor had he fled away

Whitter he could return, and her sad mind,

Tortured with hope and fearing soon did lapse

Into slow madness, which none did perceive.

She used to smile at times, at others frown;

She never wept. And every day she went

And sat in silence at the rustic stile.

And there she work’d or dreamt; now and then

Looked up and down the road, then worked again;

Now, when some distant sound upon her ears

Struck, she leaned over with her listening head

At a sad poise, while o’er her countenance came

A sad expression of expectancy,

Which faded soon, and left her disappointed.

Yet she desisted not, and when the day

Merged slowly into darkness, she retired –

Retired, but sat till midnight’s sullen hour

Struck to her heart, at that small window which

O’erlooked the road from far. Then to her sleep,

Her troubled sleep she went and dreamed of him.

[36r]

Old Castle – 8

And so in hopelessness she grew to age

In quite madness ever, till at length

She died and as she died the two first tears

Of all that silent woe down her pale cheeks

Trembled. Even as they took her to her grave,

Even as in the dark earth her coffin sank,

Out of the extreme sinking of the road

An old man came with hurrying steps unsure.

‘Twas he… And here, explaining no more, they

Who told the tale did sob.

Frail things of earth

Useless and frail, unless at times to point

Their awkward moral, or at least to show

The littleness of life and love, to mask

Man’s great, persistent, cruel vanity.

(1904).

VII.

This was the happy joyous throng. One was

Of whom I have not spoken; he indeed

Far diff’rent to them; nor had he the strength

Which as their ancient boast; his countenance

Adorned him not, his limbs and head disform

Provoked the scorn of all. Nor was this all,

For when he spoke he halted, and his words

Hung, like a fool’s, upon his thin-lipt mouth.

None had for him a word of comfort; he

[37r]

Old Castle – 9.

Wandered alone along the fields; the birds,

They fled not at his touch, for he was kind.

His weakly frame and his sick mind were not

Much fit for arms, and he indeed abhorred

The lust of man for man’s flesh, when he heard

The chronicles of fights.

(1904).

VIII.

He had learnt

To look on Nature well; and fields and flowers

And handiwork of God and man he thought

Had that no meaning; he would often pore

On man, would list in stillness to strange sounds

In dead of night; until, one fatal day,

As he had looked, the sudden meaning flashed

With lightning violence on his open mind,

Till he recoiled before it. Now he knew

And was more deep in ignorance than before.

[1904.]

IX.

Then o’er his mind and soul there crept

A sighing weariness of life, that spread

From mind to mouth and limb, that madness brought,

And sullen silence and torpidity.

[1904]

[38r]

Old Castle – 10.

X.

“I go from thee,

My native land, in pain, as one that leans

Dim-eyed and chill upon the vessel’s poop,

Leaning and watching with an unknown dread

The rushing waters and receding shore.

But through that mist of motion yet do come

Memories of life abandoned, sweer as sounds

To lonely ear the intermitted chime

Of distant merry songs, which now the blast

Cuts off, now leaves to pass, as it grows slack”.

(1904).

December

XI.

As doth a tree, silent and sure they grew –

Their deeds soon rang along the wide, long land

Until they reached their climax, when they fell,

As they were human; swift indeed yet long

Was their own fall, and dread; for those that rise

Higher, the greater is their fall at last.

And as these were but men so did they fall.

Whither by prowess they had risen, thence

They fell, even as that over-bold sun-child

Who with misguided chariot wrought to earth

Varying mischief, whom all-potent Jove,

With madden flash that darked his parent orb

Struck, when from thence he fell in headlong flight -

[39r]

Old Castle – 11.

Sheer downwards fell, and in his sweeping train

The lesser orbs he drew; from th’upper air

On to the clouds, from cloud to cloud he fell,

And from the clouds along the cloudy air

Crashed with a splash enorm into that stream

Which ever bears his name, whose spray upbeat

Assuaged the dust along the Lybian plains.

(1904, June)

XII.

Things of earth,

Oh, they are frail and useless, but in them

Musing I can forget my many pains;

All thought that aches, all tears I shed for man,

All woes, all longings do I sink among them.

Considering them my thought more pains, hence I

Through fearing, long to close mine eyes in easy death,

But, as I know not death, I suffer more.

Oh, mystery of man, how thou art sad

In all thy depth! How horrid is thy face

Wound with the veiling of mortality;

A thing too deep for words, too great for thoughts,

The life of man, and dreadful to the mind

That cannot grasp. Consider well thyself,

Thy frame and everything around, thy joys,

Thy pains and all – is there not something droll,

Horrid beyond expression in thyself.

[40r]

Old Castle – 12.

Say not therefore: “these are but things of earth

And things of small import”, for mortal things,

Full of sadness of all mortal things,

Have taught me much; from them I learnt to think

Sweet-bitter thoughts, I learnt from them to weep

The cruel fate of man. – Put upon earth,

Swayed by a thousand passions, cares and woes

Shown all his joys, by taste acceptable –

Yet often ruled by tears; though born a fool,

Raised to the highest point of natural thought,

Thrust into thinking’s light, and then at last

Plunged into eternal darkness… What! to die!

‘Tis sad indeed, to shake from us in pain

This garb of life and keep an inner cold;

We scarce can deem it true. What! that this frame

Thrilling with pleasant sense shall e’ver be cold!

And shall these veins, that bear the blood that makes

The lust of life, be dead also and gone?

… To think that we –

We, in whose throbbing veins the lust of life

Runs ever, bubbling in its pleasing sway,

Must turn to nought and lies us dead and cold!

Horrible thought! to rest us cold and stark!

Myself I wish not heaven, save that in death

I were imprisoned in the lengthening winds

Sensèd to blow about; I would desire

[41r]

Old Castle – 13.

Ever to taste the feeling of the earth,

To feel the glow of life, warmly to see,

As if with eyes, the myriad things that joy

Our sensuous vision, to perceive allwhere

The scattered perfume of all flowers, to hear

The sounds conjoining of a mighty world.

But that it must be so, I would not lose,

Racked as I am with pain, this glowing frame,

The senses’ pleasure, and this boundless mind,

These unexampled instincts, and these thoughts

That think to stagger through futurity.

Alas! to lose with mind that knows it well

The sweetest pleasures of the teeming earth,

The soft spiced winds that murmur through the spring,

The sight of vernal flowers, or the voice

Of the far river flowing through the trees.

And if all here on earth be dust and nought

And shall be lost in some uncertain end

And lost for e’er, wherefore the dear creations

Of costly minds, wherefore these minds themselves,

Wherefore a Milton’s or an Homer’s fame?

Nay nought shall die! All liveth and shall live

Looked in an immortality past through…

I lose expression in my thought’s excess

And my words fail out of desire to speak

Things I conceive not. But I know not death.

[42r]

Old Castle – 14.

I pounder, and my being fails. These flowers,

These summer fields, these birds whose festive song

Perfumes the aural sense – these are to me

A joy immense that fills my crazy soul,

Intoxicated with its melancholy,

Even to overflowing, till the tears

Unasked, unchecked must gush from my sad eyes –

And then my life is sweet. Ah fields and flowers,

Yet that enthral my senses, can I think

You must be lost to me or I to you?

That I one day shall part from ye, that I

Shall e’er again you meet; ah, all perdition!

Here lies all pain! I would with pleasure die

If with my breath and being I lost not

These things of earth that are my pain and joy,

That fill my soul with sweet and sad content.

I would fain die – ay – if death were not death,

Or if… I know well… My weighted thoughts

My straining mind desert and fail my lips

And fly the efforts of the scribbling pen.

(1904, 1905)

It may be good

To live for e’er in heaven, to live among

Angles and saints, but I would live on earth,

On sinful earth would live.

[43r]

Old Castle – 15.

XIII

All things that are on earth and form a part

Of the great visual universe I thought

At one time natural and true. But now

I have awakened to the emptiness

Of their truth. Now do I feel all within me

Inspired. My frame and soul I keep apart

For me I leave behind, with th’other soar

The pinnacles of rapture.

There is something in Nature that outweighs

My poor expression and to which e’en thought

Seems small and weak; how great then must it be!

I know not what it is, but I can feel

Its power and hear its voice in everything.

Thus when I walk the fields at early morn

It finds expression in the meanest sight.

The blades of grass, the flowers that raised glow

Upon the sward, the gentle plants, the trees,

The housewife ants and working bees, the birds,

The simple flocks and grazing herds disperst.

Nothing is dumb, for everything can speak

And all but gives expression to that voice

That lies in Nature, from the smallest atom

Seen by the mind alone, to the rough sea’s

Tremendous voice that howls, and the rude storm’s

Might terrific that sways the growing trees.

[44r]

Old Castle – 16.

Nothing is dumb: the winds in fearful rush

Speak and so speaks the river’s gentle flow.

Nor need these voice to speak; to the mind’s ear

Alone oft is the voice perceptible –

Thus if the things I see can so well speak

Many a thing can speak that is unseen.

Day, morn and eve and night can speak to me;

All tell me secrets and all are conjoint

In being the expression of great Nature’s voice.

And yet though everything can have a voice

And through that voice to me be far more great

Than any voice, it is yet strange to say

That silence speaks far more than anything.

When sleep or death relieves the world around,

Some giant voice within me moves its tones

Awful and dread, and kindles in my mind

A thousand trains of thought, makes me to see

How weak is man, then in a whisper full

Of strangest power that weighs my troubled heart

Tells me how great man is and forces tears

Up to my frightened eyes. When I retire

Within myself, and think to be alone

Lo! from within me comes that awful voice

And higher rises till ‘tis torturing. I

Cannot fly from it for it is my conscience.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

[45r]

Old Castle – 17.

Oh, voice immense, whose voice art thou? whose tones

Are those that speak in emptiness and rise

Above all sounds, above the storm’s great might.

To which the sea must yield in majesty?

And who art Thou whose might all earth pervades

And all space, time and all eternity?...

[1904, June].

XIV.

But I had learnt, closeted with my soul,

To observe and feel the inward soul of things,

And treasured vaguely intuitions. Feeling,

I thought – for feeling is unfeatured thought –

Often, and withing me a melody

Of thinking wandered, as a careless hand

With backward sweep that strikes the many chords

Of a harp idly makes.

At length I felt

One day a sourceless joy, because I saw

In all around the vestige of a Thing

That never dies, a Being that pervades

All things that are, whose thought is allwhere seen.

And I have wept with joy for that I found

This soul that gives the lustre to the sun,

That makes the rose to bloom, that stirs the stream,

That moves the sea and dwells in inner man,

That gives life to the world and shines the stars

[46r]

Old Castle – 18.

Is one; and I have found all things that are

In form but differ, are embodiments

Of this great soul that thrills the universe.

And I, grown wise, have seen, have felt, nor dared

To soil by thought, the fulness of this life;

And I have learnt to look upon all things

As doubtful forms, and I have noticèd

In them that soul that interpenetrates

The mazy ways and laboured labyrinths

Of man and all the world, and of which they

Are but the forms material, as this frame,

This mortal frame that rots when it hath gone.

Can I more happy be? is aught more great

Than is the presence of these thoughts sublime

That elevates my heart; to feel and touch

The spirit-essence magic that instils

Its thought and love into all things, that dwells

Alike in field and crag and work of man,

That never leaves the light of suns etern

Nor e’er the sunless end of fallen worlds.

[1904][October]

XV.

What is a flower?

To thee a thing that buds and blooms and dies,

Emblem perhaps of human things; to me

An atom colour-gist[2] of life etern.

[1904][December]

[1] Is seen and earth fall the awing shades of night. /[V-Is seen and earth now feels the oppressing gay of night.]\

[2] colour-gist /known\

Classificação

Dados Físicos

Dados de produção

Dados de conservação

Palavras chave

Documentação Associada

Publicação Integral: Fernando Pessoa, Poemas Ingleses, Tomo II – Poemas de Alexander Search, Edição de João Dionísio, Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional – Casa da Moeda, 1997, pp. 148-159, 183-200.